An Intro into Ontology Logs (Ologs)

An Intro into Ontology Logs (Ologs)

What is an olog?

An olog, short for ontology log, serves as a rigorous framework for knowledge representation, grounded in the principles of category theory. This mathematical foundation focuses on abstract entities and their interconnections, providing a robust structure for modeling knowledge domains. Ologs are composed of objects, which denote specific concepts or types, and morphisms, which describe the relationships or functions linking these concepts. This setup ensures that ologs are accessible and interpretable both by humans and computers, making them invaluable tools for clearly articulating complex ideas. They facilitate seamless communication across diverse fields of science and scholarship, and between human intellect and computational logic. Utilizing ologs enables the orderly arrangement of information, the definition of intricate concept relationships, and fosters a deeper comprehension of the subject matter at hand.

The Greenwood Ecosystem

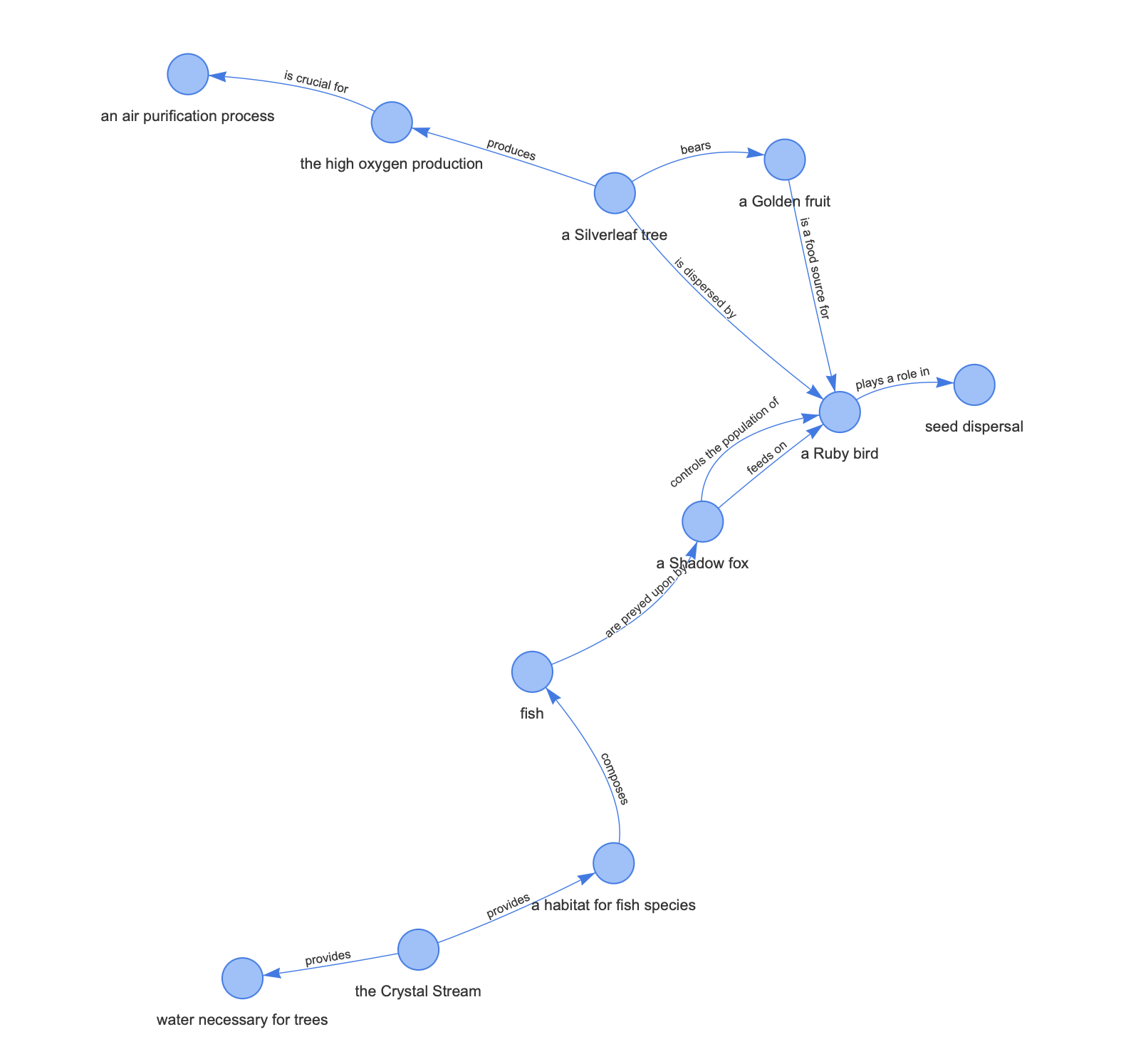

In the heart of the Greenwood Forest lies an intricate and bustling ecosystem, a testament to nature’s complexity and interconnectedness. Imagine, if you will, an effort to encapsulate this vibrant community in a structured form of knowledge representation, known as ologs. Through ologs, we embark on a journey to map out the Greenwood Ecosystem, capturing the essence of its flora, fauna, and the myriad relationships that bind them together.

In the Greenwood ecosystem, various species interact in a delicate balance. At its core are three primary components: the Silverleaf trees, the Ruby birds, and the Shadow foxes. Silverleaf trees, known for their high oxygen production, are crucial for air purification. They bear Golden fruits, which are the main food source for the Ruby birds. These birds, characterized by their vibrant red feathers, play a vital role in seed dispersal for Silverleaf trees. Shadow foxes, elusive nocturnal creatures with dark fur, are key predators in this ecosystem. They primarily feed on Ruby birds, thus controlling their population. The ecosystem also includes a river, the Crystal Stream, which provides water for the trees and a habitat for various fish species. These fish are occasionally preyed upon by the Shadow foxes. This interdependence creates a complex web of relationships that sustain the Greenwood ecosystem, demonstrating a balance between predation and mutual benefit.

Objects and Morphisms

Objects in ologs serve as foundational elements, representing distinct concepts or types within a specific knowledge domain. They act as the vertices in the graph-like structure of an ontology, encapsulating the individual entities or ideas of interest. The process of identifying and defining these objects is crucial, as it establishes a structured vocabulary that delineates the components of the ontology. This systematic identification and definition of objects ensure that the ontology can accurately and comprehensively represent the knowledge domain it is intended to capture.

Morphisms, on the other hand, are the edges in the olog’s graph structure, representing directed relationships or functions between objects. They specify the manner in which one object is related to or interacts with another, thus articulating the dynamics and connections that permeate the ontology. Morphisms make the complex web of dependencies and interactions within the ontology explicit, revealing the underlying structure and facilitating a deeper understanding of the knowledge domain.

Together, objects and morphisms constitute the backbone of an olog, providing the means for a precise and coherent representation of a knowledge domain. This combination offers a robust framework for mapping out complex systems, enabling the elucidation of intricate relationships and promoting comprehension across various fields of study. By leveraging the structured representation that objects and morphisms offer, researchers and practitioners can navigate and analyze the complex interplay of concepts within an ontology, thereby enhancing understanding and facilitating knowledge discovery.

- Objects:

- Silverleaf Trees (key oxygen producers and bearers of Golden Fruits)

- Ruby Birds (vibrant red-feathered birds, consumers of Golden Fruits and seed dispersers)

- Shadow Foxes (nocturnal predators of Ruby Birds)

- Golden Fruits (produced by Silverleaf Trees, food for Ruby Birds)

- Crystal Stream (provides water to the ecosystem and habitat for fish)

- Morphisms:

(trees bearing fruits) (birds eating fruits) (foxes hunting birds) (animals drinking from the stream)

Functors

Functors in ologs map one knowledge domain to another, preserving object and morphism structures, akin to translating ideas while maintaining their relationships, enriching linguistic and conceptual understanding. To illustrate the concept of functors in our Greenwood olog, let’s introduce a hypothetical scenario involving two ecosystems: the Greenwood ecosystem and a Desert Oasis ecosystem.

- Greenwood Ecosystem Olog (original olog):

- Objects: Silverleaf Trees, Ruby Birds, Shadow Foxes, Golden Fruits, Crystal Stream.

- Morphisms: Produces, Consumes, Preys on, Hydrates.

- Desert Oasis Ecosystem Olog (target olog):

- Objects: Palm Trees, Desert Falcons, Sand Foxes, Dates, Oasis Water.

- Morphisms: Produces, Consumes, Preys on, Hydrates.

A functor

The morphisms are preserved in a similar manner. This functor

Natural Transformations

Natural transformations in ologs show how meaning persists across frameworks, offering a systematic way to study complex system links. Using our greenwood example lets illustrates how natural transformations can facilitate a transition between different perspectives in an olog, preserving the logical coherence across these transformations.

- Botanical View Functor (F):

- Focuses on plant-related aspects.

- Maps objects like Silverleaf Trees to their botanical characteristics (e.g., Leaf Structure, Growth Patterns).

- Maps morphisms to processes like Photosynthesis or Fruit Production.

- Animal Behavior View Functor (G):

- Concentrates on animal behavior.

- Maps objects like Ruby Birds and Shadow Foxes to their behavioral patterns (e.g., Feeding Habits, Hunting Techniques).

- Maps morphisms to activities like Migration or Predation.

A natural transformation

from to would consist of a series of correlations connecting the botanical aspects to animal behaviors.

For example:

Limits and Colimits

Limits and colimits enriches ologs with structures capturing complex relationships. Limits serve to organize disparate entities into cohesive systems, effectively mirroring the nuanced links found in real-world scenarios. Limits, akin to meticulously designed layouts, gather and align various elements—objects and morphisms—into coherent structures. Conversely, colimits facilitate the merging of distinct types, fostering rich, expressive representations.

- Limit Example - “Ecosystem Stability Point”: A balanced Greenwood state with Silverleaf Trees, Ruby Birds, Shadow Foxes.

- Pullback for “Ecosystem Stability Point”:

- Let

represent the relationship ‘Trees provide food for Birds’, and represent ‘Birds are preyed upon by Foxes’. The pullback, , would represent the unique interdependency of these species. This pullback ensures that each element accurately reflects the balance of the food chain and population control within the ecosystem.

- Colimit Example - “Integrated Habitat”: Describes merging species (Silverleaf Trees, Ruby Birds, etc.) into the Greenwood ecosystem entity.

- Pushout for “Integrated Habitat”:

- If

represents the role of each species in the ecosystem, the pushout, denoted as , would represent the collective habitat. It would ensure that for any other entity interacting with individual species, there exists a unique relationship that captures the overall ecosystem dynamics.

Adjunction

Adjunction in ologs reflects a “perfect match” between categories, with key functors (F) and (G) acting as bridges, preserving core structures. This reciprocal link is solidified by natural transformations, modeling equivalences between systems.

- Greenwood Ecosystem Olog:

- Focuses on natural ecological processes and interactions.

- Urban Environment Ecosystem Olog:

- Concentrates on urban wildlife and plant interactions within a cityscape.

An adjunction can be established between these two ologs using a pair of functors:

maps concepts like Silverleaf Trees to Urban Trees, and Ruby Birds to City Birds. would map in reverse, translating urban ecological elements back to their natural counterparts.

This adjunction illustrates the correspondence between natural ecosystems and urban ones, demonstrating a conceptual bridge where processes and interactions in one can be translated to the other, preserving their ecological essence.

Monoid and Group

To apply the concepts of Monoids and Groups to the Greenwood ecosystem, let’s consider the cyclical patterns of ecosystem dynamics.

- Monoid in the Greenwood Ecosystem:

- Objects: Different states of the ecosystem (e.g., Flourishing, Dormant, Recovering).

- Morphisms: Transitions between these states (e.g., Seasonal Changes, Ecological Disturbances).

- Monoid Structure: Represents the sequential changes in the ecosystem. For instance, if

is the set of all ecosystem states and is the transition, the monoid can be described as . There is an identity state (e.g., a Stable state), where for any state .

- Group in the Greenwood Ecosystem:

- Group Structure: Introduces the concept of reversible changes. Each state

has an inverse , indicating a return to a previous state or condition.

For example, a disturbance event and its remediation could be inverses, satisfying

Monads

To demonstrate Monads in the context of the Greenwood ecosystem, consider a Monad that encapsulates the lifecycle of the ecosystem, encompassing various stages and transformations.

- Objects: Different stages of the ecosystem (e.g., Germination, Growth, Maturity, Dormancy).

- Morphisms: Processes or changes that transition the ecosystem from one stage to another.

In categorical terms, a Monad

- A functor

(transformation of stages). - A natural transformation Unit

(introducing a new cycle of the ecosystem, like a germination stage). - A natural transformation Multiplication

(combining two consecutive stages into a singular, cohesive process, like merging growth and maturity).

This Monad

Modularity and Composition

- Modularity: Each sub-ecosystem (like the forest area with Silverleaf Trees, the river ecosystem of the Crystal Stream, and the habitat of the Shadow Foxes) can be represented as an individual olog. These ologs contain specific objects and morphisms relevant to their area.

- Composition: These individual ologs can be composed to form the larger Greenwood ecosystem olog. This composition reflects the interconnectedness of the sub-ecosystems, creating a holistic view of the entire ecosystem.

Mathematically, if

This shows how complex ecological systems can be constructed from simpler, modular components, demonstrating the principles of modularity and composition in ologs.